Traditionally, health and safety efforts have focused on the physical parts of an organisation. The environment in which people work, along with the tools, equipment, machinery and substances that are used to perform work, should be risk assessed and any hazardous conditions managed as effectively as possible. This requirement is enshrined in WHS legislation, both at a general level in the form of duties placed on the collective entity operating a business or undertaking (PCBU), as well as obligations aimed at individuals (i.e. officers, workers and visitors).

In addition to the physical components of WHS, organisations must also ensure that systems of work—processes, procedures, communication and information flow—are appropriately managed and do not carry any undue risks. We see this within WHS legislation in the form of ‘due diligence’, which is aimed at senior leaders to ensure that WHS is actively considered when major strategic and operational decisions are made.

Despite the existence of WHS legislation and safe systems of work, incidents still happen. In some workplaces, hazards continue to be inadequately managed and controlled because of gaps in, lapses, or violations of safety performance standards by individuals.

Many factors influence the safety performance of individuals in an organisation. Some are clearly outside the direct control of leaders, such as personality and similar individual traits or differences. However, others can be influenced, if not controlled, through the organisational setting or context that is established around employees. One of the most important and studied contextual aspects is safety culture.

Safety culture

Safety culture is the collection of deep assumptions, values and beliefs that are shared by a group of people in a high-risk industry (Griffin & Curcuruto, 2016). It can be somewhat murky and difficult to decipher, particularly for those embedded within it—outsiders are often better equipped to measure an organisation’s safety culture (Schein, 2010). In relation to safe systems of work, safety culture exerts constraints, boundaries, and guidance over how people should think and behave when it comes to doing work (Casey, Griffin, Harrison & Neal, 2017).

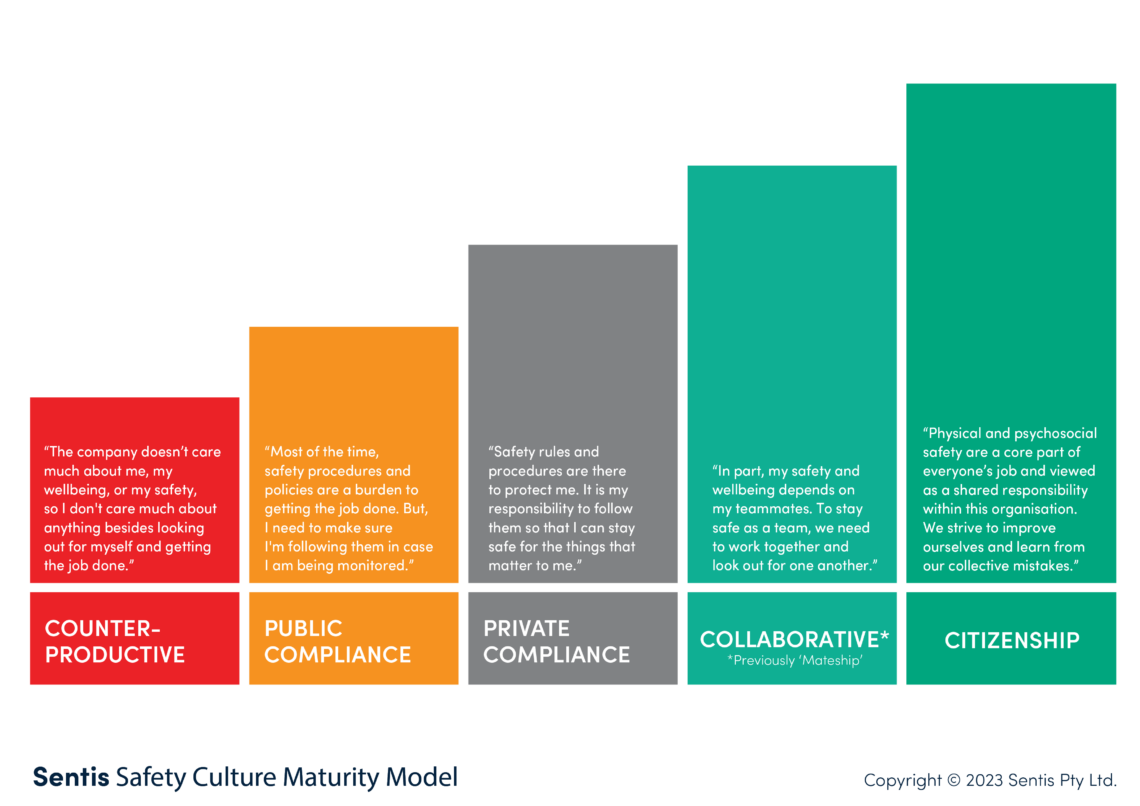

The nature and effects of safety culture change depending on its level of maturity (Casey & Krauss, 2016). At one extreme, a safety culture can be described as counterproductive, whereby safety is not a shared priority and is routinely put behind other goals such as productivity. At another extreme, a safety culture can foster citizenship, where employees go above and beyond what is expected in terms of safety performance. Establishing a safety citizenship culture leads to behaviours that help a company improve how it manages WHS and achieves a level of safety performance above compliance.

With this in mind, it follows that a company’s safety culture plays an important role in shaping compliance with WHS legislation (Sherriff, 2011). At the highest level, there is a foundational duty of care that requires PCBUs to implement hazard identification and management actions as far as is reasonably practicable to reduce risk in the workplace (S19, WHS Act). Arguably, demonstration of such care in a genuine way is the foundation of a safety culture. Through repeated demonstrations of safety commitment (e.g. prioritising safety over production, investing resources in safety equipment), a positive safety culture will be built over time.

Legislation and safety culture

S27 of the WHS Act places a duty of care on officers (senior leaders) as individuals. This duty is called ‘due diligence’ and refers to specific actions that officers must take such as keeping up to date on WHS issues and information about the work system. In a safety culture characterised by fear, mistrust and external supervision as the driving force of motivation, an officer’s ability to uphold this duty could be compromised. Workers are likely to withdraw from leaders and be less willing to share information. Investments must be made in the safety culture to ensure compliance and more importantly, meaningful WHS outcomes following compliance.

Another legislated domain of WHS that has implications of safety culture is consultation. S47 of the WHS Act states that PCBUs must consult with workers on WHS matters, in particular identifying and managing hazards, and making decisions that affect employees’ WHS. High quality communication, including two-way consultation, is a hallmark of a positive safety culture (Vecchio-Sadus & Griffiths, 2004). Employees at all levels are given the opportunity to contribute to WHS decision-making and asked for their ideas and experiences so that WHS can be improved.

Impact of quality consultation

Our own research conducted using our Safety Climate Survey (SCS) aggregate database (a snapshot of the underlying safety culture at a point in time) reveals the importance of high quality WHS consultation. The SCS measures employees’ perceptions of consultation and collaboration with senior leaders around WHS matters.

Our analyses show that after accounting for position and experience in industry, the quality of WHS consultation predicts whether employees comply with WHS standards and processes at work. Higher quality consultation was associated with more frequent safety compliance behaviours. These results suggest it would bode well for companies to measure their safety culture so that the quality of consultation processes can be identified and improved if needed.

Moving towards safety citizenship

Moving a safety culture takes investment of resources and patience. Leveraging diagnostic measures optimises this investment by identifying specific opportunity areas. One of the common levers to begin a shift in safety culture is leadership. Leaders influence the underlying safety culture by challenging existing beliefs and values, and setting the standard that others should follow. In particular, safety leadership soft skills enable leaders to achieve safety culture change more efficiently and with sustainable impact. Incidentally, building safety leadership skills is also likely to improve compliance with legislation—in particular, S27 ‘due diligence’ and S47 ‘consultation’.

Although safety culture is not yet explicitly mentioned in the Australian harmonised WHS legislation, it is a national strategic priority of Safe Work Australia and a number of state regulators (an example being Workplace Health & Safety Queensland’s Safety Leadership at Work program). In some domains, safety culture is explicitly mentioned, such as the Transport (Rail Safety) Regulation (2010). Other legislation states that achieving a safety culture is an implicit yet foundational goal (e.g. Bus Safety Act, 2009). Given that safety culture is wrapped up in compliance, businesses of all sizes should be asking themselves: is our safety culture helping or hindering compliance, and what can we do about it?

References

- Casey, T.W., Griffin, M.A., Harrison, H.F. & Neal, A. (July, 2017). Safety culture and climate: Integrating psychological and systems perspectives. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology.

- Casey, T.W. & Krauss, A.D. (April, 2016). Applying I/O science and methods to diagnose safety culture maturity. Paper presented at the SIOP Annual Conference, Anaheim, California, USA.

- Griffin, M. & Curcuruto, M. (2016). Safety climate in organisations. Annual Review of Organisational Psychology, 3(1), 191-212.

- Schein, E. (2010). Organisational culture and leadership. San Francisco: John Wiley & Sons.

- Sherriff, B. (2011). Promoting effective health and safety leadership: Using the platform in the model Work Health and Safety Act.

- Vecchio-Sadus, A. & Griffiths, S. (2004). Marketing strategies for enhancing safety culture. Safety Science, 42(7), 601-619.